BluesWax Sittin’ In With

Dick Waterman

Part One

By Bob Gersztyn

Not all of the elder statesmen of the Blues are legendary Blues musicians. Some are simply legendary. BluesWax friend Dick Waterman is just such a man. We sent Bob Gersztyn to speak with Waterman.

Enjoy.

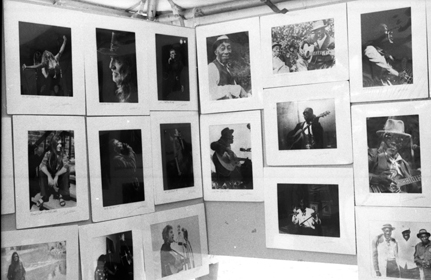

This past July when BluesWax attended Portland, Oregon’s 18th Annual Waterfront Blues Festival, I interviewed agent, archivist, manager, photographer, producer, promoter, writer and Blues Hall of Fame member Dick Waterman. Since Waterman is the only person ever inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame who isn’t a musician or record company executive, I figured that talking to him would be just as important as Friday’s headliner, Buddy Guy. In fact, Waterman was Buddy’s manager at one time. Waterman just published his first book, Between Midnight and Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archive. It contains about a hundred photographs that he took, going back to the early 1960s, along with essays about the subjects. Some of them are Ray Charles, Eric Clapton, Reverend Gary Davis, Buddy Guy, Mississippi John Hurt, Mick Jagger, Skip James, Janis Joplin, B.B. King, Bonnie Raitt, and Junior Wells, to name a few. He got to know the subjects so intimately that he eventually left the camera behind to concentrate on the relationships. It was with all this in mind that I cautiously approached Dick Waterman while he was signing one of his newly purchased books. When my turn in line came, I told him that I would like to interview him about the Blues for BluesWax, and he graciously agreed to do it. So we set up a time and met behind one of the unused stages, while live Blues raged on a more distant one.

Bob Gersztyn for BluesWax: How did you first become aware of the Blues?

Dick Waterman: I was born in the mid-1930s, so by the late forties I was thirteen or fourteen years old I loved Louis Armstrong. So I think Louis Armstrong really started it for me and I saw Louis in person, and then I got into a few things like Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and some things with this guy named Jack Teagarden. I saw Jack Teagarden. I witnessed some absolutely great vocalists and I think that Teagarden is probably one of my favorite vocalists of all time. So I started with Louis and Dixieland, and then I loved Calypso music from the Caribbean, like Mighty Zebra and Mighty Sparrow. Then I went in and out of the army, and I went to Cambridge in the early sixties. So going to New York I had seen Reverend Gary Davis, who was on the scene, and I had seen Josh White, but I think that one of the watershed incidents for me was at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival where I saw Mississippi John Hurt, who had recently been rediscovered and brought to Newport. I think his music and his personality and his aura just captivated me, so although I had heard really great Bluesmen before I heard John Hurt at Newport in 1963, I think that was a real significant event for me.

BW: How did you first become a photographer?

I was a sportswriter in the fifties and I had my own camera and I’d been doing sports photography. So I didn’t need any training or background in composition, exposure, film speeds, or shutter speeds, because I already had that experience when I came to music. I’m not sure when I started, but I remember Newport in 1963. I have a Bob Dylan, a Mother Maybelle Carter, and lots of stuff from Newport 1963. I don’t know if I was shooting before then, but Newport ’63 are my first printable Blues images.

BW: Do you do your own processing, and what kind of film and chemistry do you use?

DW: When I started in the 1960s, I did all my own developing and printing. We were entirely Kodak: Kodak black and white and Kodak color. We shot very little color. Black and white was sixty cents a roll, and color was about a dollar. That’s a lot of money and we could process our own black and white, two rolls at a time, on the floor in the bathroom. So if you went to a festival and came back with a lot of film, stay up all night we’d developing two rolls at a time. Color work had to be sent out to a lab and we didn’t have that money, so we shot

BW: What film were you using, Tri-X?

DW: I shot PlusX for daytime and Tri-X for night concerts. We didn’t push anything. We didn’t develop anything to be pushed. The PlusX is 100 and the Tri-X is 400. If we knew we were going to have bright sunlight, and we were going to be able to finish the roll, we had something called PanatomicX, which had 40 ASA and was very, very fine grain. But, as I looked at my daytime prints from the 1960s, I can’t tell which is PanatomicXand which is PlusX. It’s all fine grain.

BW: Did you use the same developer for all of them?

DW: Yeah, whatever it was. We just went into the camera store and bought standard developer and fix.

BW: Are you at all related to the Richard Waterman, who did a lot of music writing back in the twenties and thirties?

DW: No. We not only have the same last name and same first name, we have the same middle name! We’re both named Allen. Richard Allen Waterman, and it’s really confusing. He did a tremendous amount of work in the Library He was alive in the sixties, and I kept getting invited to participate in the German of Congress, and did a lot of historic writing on African Caribbean music. /American Folklore, and I would say, no you’ve got the wrong guy. I never met him, but he was a professor at Wayne State University, in Detroit, Michigan, before he moved to the University of South Florida. I had Son House at Wayne State University, in 1965, and somebody said that he came into the back of the room to watch a little bit of the show and then left, but I never met him.

BW: How did you get into the management and promotion part of the music?

DW: I promoted Mississippi John Hurt in February 1964. Then I promoted Booker White. Then we got to talking to Booker about old Blues men like Robert Johnson, Charlie Johnson, Son House…and he said, Oh, I saw Son House coming out of a movie theater. So that sent me and two other guys, Nick Perls, and Phil Spiro, down to Memphis looking for him. The truth was that Booker had not seen him, he was lying. Once we were down there we heard that Son had done his recordings in a little town called Robinsonville, Mississippi. So we went down there and we backtracked him through friends and relatives, and ultimately we found out that he was living in Rochester, New York. We got a phone number there and we spoke to him. So he was living in Rochester and we were down in the Mississippi Delta. So we left the Delta and went up to Rochester.

BW: When you were first going into the Deep South in the 1960s, did you ever run into any racist persecution because of trying to promote Black music?

DW: When I was in Mississippi looking for Son, we ran into some white guys in pickup trucks. Since we had New York plates on a yellow Volkswagen, they thought that we were down there for voter registration and stuff like that. We told them that we just came down to hear the Blues music and record some of these Bluesmen. So they were sort of amused and kind of befuddled, and they would say, You come all the way down here from New York City, down here to Mississippi, just to hear that nigger music? And we said, Yes, sir. Then they say, Well you welcome to it, and there’s a lot of it, because there ain’t a porch here that ain’t got a nigger on a chair playing that music. The music was held in low esteem, and with low value. It was not racist, it was just a befuddled confusion that we had come so far, to hear what was just a common commodity that they held in such low regard.

BW: What did you think when the British came to America, like the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton, playing the Blues and becoming Pop stars with it?

DW: The black Bluesmen figured simply, if you can play it, he’s welcome to it, that’s all. I think it was more white people who felt young English kids are getting rich on black peoples’ money and they would go to the Bluesmen and they would plant the seed of negativity. They would say, These young white kids are getting rich on your music, and you’re getting ripped off. You should be angry. So they planted that discord of anger, but Muddy [Waters] genuinely liked Eric. No doubt about it. And he genuinely liked Keith [Richards] and Mick [Jagger]. After they hit, it changed his lifestyle. He made money, he became well known, he toured at a higher level. The same with Wolf. Through the years Wolf, and Hubert Sumlin’s, got really well known. The idea that people were getting ripped off, all of that is about copyright and publishing. That’s where the real money is and a lot of black people got really, really rich, off of white people doing their material. Look at how rich Willie Dixon got, or Jimmy Rogers, after Eric Clapton did two of his songs. Then Stevie Ray Vaughan did Buddy Guy’s Mary Had A Little Lamb.A lot of black people have done very, very well when white artists recorded their songs. If you had your house in order with copyright and publishing; a Skip James song is done by Cream or a Fred McDowell song is done by the Rolling Stones. If you have your publishing and copyright house in order they can make money for you. It isn’t up to me to be the loyal guardian at the gate with white boys singing black music. Because I think that if you can play it then you’re welcome to it, and I know the black people feel the same way. If you can play it, you’re welcome to it.

BW: Why don’t you talk a little about your book projects like Midnight To Day, the book of your photographs that you had published.

DW: Midnight To Day is about fifty essays, and about ninety to a hundred photographs, with the exception of a Bob Dylan, that’s all Blues. But my shooting collection is deep into Folk, Jazz, Bluegrass, Country, old timey Rock ‘n’ Roll, Cajun Zydeco. The collection is very, very vast. I wrote a B.B. King biography that will be out in September [Since this interview Waterman’s book, The B.B. King Treasures, has been published], but I just wrote it, and interviewed people, and edited through B.B.’s interviews. I think that I have four or five photographs in it, but I don’t have a big photo presence in the book.

Part Two

By Bob Gersztyn

In Part One last week we were introduced to Blues historian/photographer/manager Dick Waterman Thanks for all the feedback about this obviously popular interview. This week we pick up the conversation with some discussion of the photos Waterman has taken and more. Enjoy!

Bob Gersztyn for BluesWax: How many photographs all together would you estimate that you have in your music collection, in the form of negatives and slide transparencies?

Dick Waterman: I’d really be hard pressed to guess. You go out and shoot seven or eight rolls of film, so there’s at least three hundred negatives there, then we’d shoot a lot at Jazz festivals. I don’t know. It’d have to be in the tens of thousands. I practically didn’t shoot at all from the early seventies to the early nineties because I was deep into management, but I came back to shooting in the early nineties. I have famous people that I met and knew well and never photographed. I have known Jimi Hendrix and I have known Stevie Ray Vaughan, who were both fairly good friends. It’s sort of difficult to explain…if you know someone as your friend and you just hang with them, some kind of an inner circle evolves. You’re welcome here. You’re just with them as a hanging buddy. At that point you really can’t say, Hey, man, I have to got out to my car and get my camera. Because they’re going to say, Oh no, man, you don’t want to do that because you’re on the inside. Right? Why do you want to go back outside?So I had a friendship with Hendrix and Stevie Ray, and some other people. Because I was East Coast based, I don’t have any Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe, Boz Skaggs, or any of that. I saw the Doors’ first show out of L.A. in late 1965 or early 1966. They were third on the bill to the Grateful Dead, Junior Wells, and the Doors at the Fillmore. That was a really early gig and I didn’t have my camera equipment with me, so I didn’t photograph them.

BW: What is your take on the roots of Blues and Gospel?

DW: I did not manage a single Bluesman, ever, ever, ever, who did not perform Gospel. Every Bluesman I ever worked with – ever – always performed Gospel.

BW: So are you saying that the two of them are synonymous?

DW: Skip James opened every show with a Gospel song. It was like he was paying a toll to enter. He pays his admission. He gave one to the Lord to open the night.

BW: He was a minister too, wasn’t he?

DW: I don’t know. He said he was, but I don’t know how ordained he was. Fred McDowell, of course, did You’ve Got To Believe and then there were John The Revelator, Wade In The Water,and This Little Light Of Mine.

BW: What did you think of Martin Scorsese’s program on PBS about the Blues?

DW: Blues people had been working on this thing for years by 2003. They were on this in 2001. They staffed this for years. They had a Blues office, quote The Blues PBS.They had this office in New York in 2001 and 2002. They had camera crews and they were doing photo captions and checking and double-checking, and publishing and double-checking, and copyrighting and double-checking, and photo identification and double-checking. They’d stack this stuff on and on and on and on. The number of man-hours that went into this before he picked it up is monumental. They had film crews all over Mississippi. I heard there were crews in Oxford and other cities; it went on and on and on. I actually remember this: the seventh day after Scorsese agreed to do it and the seventh day after he actually participated, people left the project; Spike Lee, Al McCracken, Michael Ackmed, Bob McFranken left. Making sure that even this thing went through so many, many, many, many changes. It should have been one night a week; like Tuesday. Tuesday is Blues night on PBS. So you get a lot of information out on it, talk about it, news groups, and then you see the show, and then you talk about it, and savor it all week. Then here comes the next episode and that lasts another week. Seven nights crashed when a lot of people couldn’t put in two hours a night for seven consecutive nights. Running it on seven consecutive nights was a bad mistake and I knew that. If you didn’t like it you didn’t read the instructions on the box because they said to you right at the very beginning, PBS has given seven directors an equal amount of resources and an equal amount of cash and they had to deliver their own personal vision and what they feel the Blues is. Nobody ever said that it was a documentary. Nobody ever said all encompassing. Nobody ever said we’re going to show you the history of the Blues. No, and if you believe that then that’s because you didn’t read the rules, which were very explicit. Seven different directors were given an equal amount of time and an equal amount of dollars, and they would bring forth their own specific vision. Scorsese was to be executive producer and not a hands-on director, but the director of the first episode left. So he had to step up and direct that episode. Eastwood came in so late that the thing ran until September and by Labor Day, which was three weeks before, after three years of planning they get to three weeks before the deadline date and Eastwood steps in to fill another gap. In other words, they had a whole lot of problems with it. But if you thought that it was going to be a documentary that would catch what you liked about the Blues and you missed it, don’t complain, because it was never intended to be that.

BW: In your opinion what are the roots of American Blues?

DW: I’m a firm believer that Blues is economic and not racial. I think that if you were white and poor, disenfranchised, living in a shotgun shack, or maybe in a truck trailer, in a poor Southern town, I think that you have more in common with your black neighbor down the tracks, who also lives in a shotgun shack or trailer, who has no money. You have more in common with them than some wealthy white guy and he, as a black man, has more in common with you than with some African American who went to Harvard Business School and now is working on Wall Street. Blues is economic.

I think that some of the greatest Bluesmen in the world were Hank Williams and Elvis Presley. They were poor white trash. They hung with Negroes, they listened to Negro music and Gospel. They liked it and played it. I spoke to older black men in their seventies and eighties who knew Elvis and said he’s a good boy. He loved the music, he loved the Lord, he loved Gospel music, he honored his mother. They’ve got nothing bad to say about Elvis. The idea that white people rip off black is ridiculous. Sure there are isolated cases, but I’m telling you that Blues is based on economics. I think Charlie Musselwhite, who was from Mississippi, moved to Memphis as a teenager, hung on the streets with Will Shay, Gus Gannon, Smiley Lewis, Booker White, moved to Chicago’s South Side, hung with Little Walter and Big Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, I think that he’s more of the genuine to-the-bone Bluesman than a lot of black guys who were more privileged. Obviously it’s my opinion, but I’ve been on the scene now for nearly fifty years. Hank William, Elvis Presley, Charlie Musselwhite, their okay, they’re

Bluesmen to me.

BW: So then the black musicians that came from middle or upper class homes and play Blues, are less Bluesmen than white musicians who grew up in poverty?

DW: There’s a difference between being a Bluesman and playing Blues songs. Big difference. Bonnie Raitt and Eric Clapton will tell you right from the get-go, to make it very clear, we play Blues songs, we’re not Bluesmen. We try and hope to honor the tradition. We hope that we’re a doorway. That when you hear me do a Sleepy John Estes you will go back there and listen to him. If you hear me do Sippie Wallace, go back and hear her. I’m not the end. I’m the means to the end. Clapton named an album, obviously that he wanted people to pay attention to, From The Cradle. If you would know me, you would know where my music comes from. These are my roots. From the cradle. I come from this music.

Bob Gersztyn is a contributing editor at BluesWax.

https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/blindmanfr/dick-waterman-interview-2005-t45490.html

When I was 19 or 20, Delta Blues Man Son House was playing an afternoon concert in the Syracuse park. I had my harmonicas with me. I had been playing blues gigs about 3 years.

I asked the manager if I could sit in with Son House. I played for him and he said “you could play the whole gig.”

I had the Columbia Son House record so I knew his material had listened to the album many times and knew that he sang a cappella sometimes. And I think I understood what my role should be, and it was that of a Catholic altar boy, (another job I knew) I knew much more testifying current was running through Son House. And I was playing to add here and there, stay out of his way and listen for his que to step up and give him a break from singing when he said, “Blow your horn, boy! Blow your horn!” All his songs were in the key of G because he tuned his Style O silver National guitar to open G for the slide. And he had to tune to the harmonica to make both of us in A440 tuning. He’d ask for the individual notes and I’d play each of them until he felt it right and we’d move on to the next string. And then we started….and ooh, and he was good. Thrilling! He was plugged into that higher ground socket. A soul shaking powerful voice, with slashing metal guitar work!!!

I did my altar boy support thing and towards the end, got off the stage for his finish with a cappella songs.

I had a “what just happen?” feeling at the end .

Nicholas Langan, Philadelphia

langannick@hotmail.com